- The housing shortage of 400,000 impacts large parts of society: will all problems soon be solved?

- Government’s ambition to build 100,000 new houses per year until 2050: a realistic target?

- A budget of €5bn is made available to support all plans. Will this be enough?

- Foundation issues are on the agenda, as funds are made available to support home owners. A serious attempt to tackle the problem or merely a symbolic first step?

Download here the pdf

Structural housing shortage explained

Before we elaborate on the impact of the government plans, we thought it would be a good idea to briefly outline the scale of the housing shortage problem. Due to the high population density and competing demands for limited space that is available, there will be a significant housing shortage in the foreseeable future. As the graph below implies, there is currently a shortage of more than 400.000 homes.

And in 2050 the housing shortage is still an issue, given the estimated shortage of 150,000 homes. The graph is based on estimates like the population growth and average size of a household, and an annual change in the housing stock of around 80,000. Given this trajectory, something needs to be done rather sooner than later.

To tackle this issue, the Dutch government is aiming to build/create 100,000 per year. But two issues need to be taken into account. First of all, adding 100,000 houses annually to the housing stock is ambitious. We will elaborate on that in the next paragraph. Secondly, one of the inputs that is used to construct the above graph is the expected population growth rate. But the fact is that the population growth has been grossly underestimated over the last decade. This is the main reason that the shortage increased during the last view years. So every time this graph has been updated, the situation has got worse rather than better. To provide some figures from the CBS (national bureau of statistics): the size of the population was 16.8mln in 2013. In 2024 that number increased to more than 18mln. So in about ten years the population increased by more than 1.2mln. To illustrate, that’s even more than the city of Amsterdam with a population of 930,000 (2024). This again underlines the seriousness of the problem.

100,000 new houses a year, is that possible?

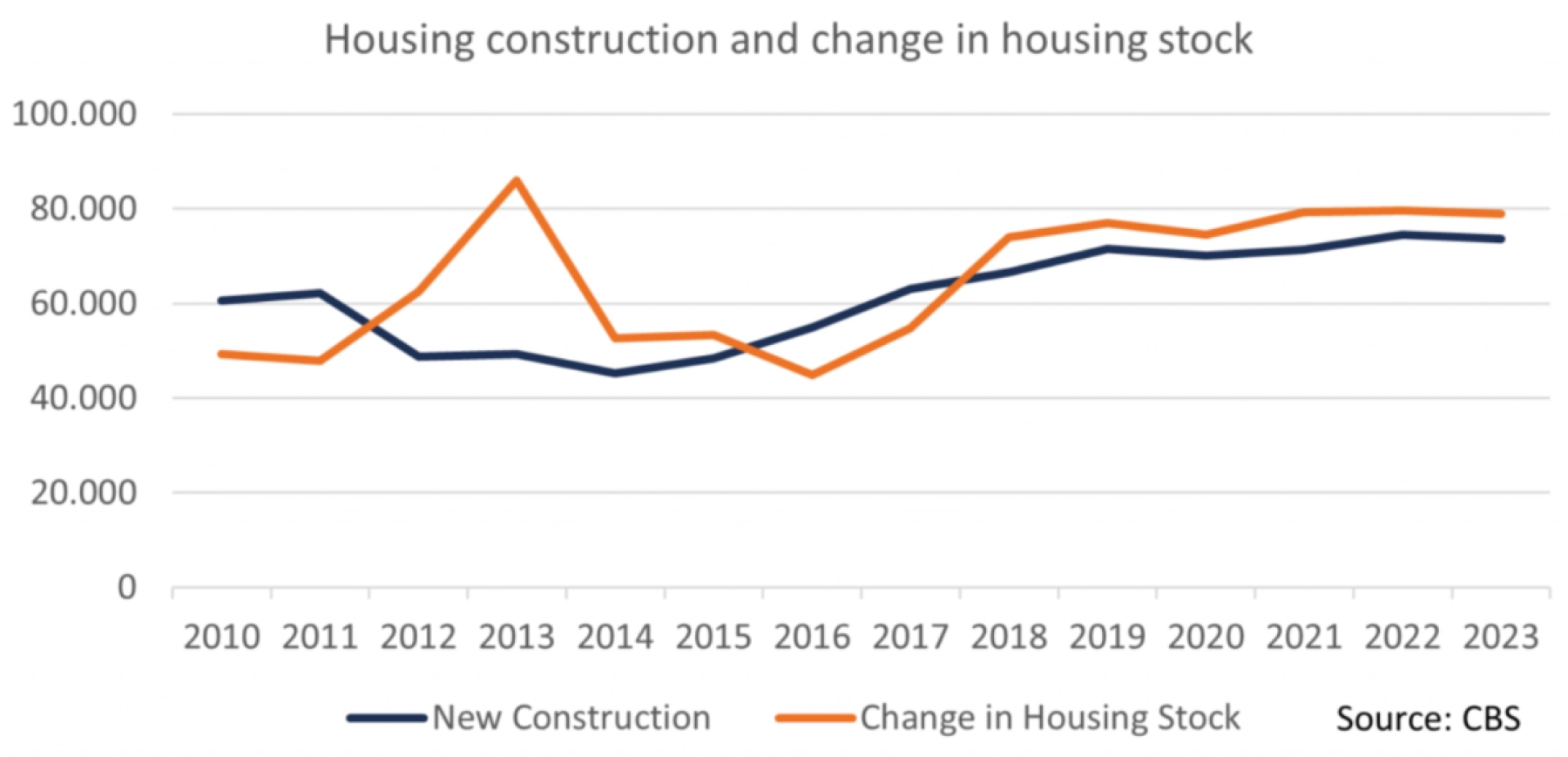

As mentioned above, the government’s main target is to create 100,000 new homes per year. We have deliberately used the word "create" here because new housing is not just new construction, but also includes the conversion of office buildings and, for example, the splitting of flats into multiple units. If we look back, say over the last 10+ years, we can see whether creating 100,000 houses per year is achievable. We would like to illustrate this in the graph below.

Focusing first on the time series for new construction (blue), it's clear that the annual construction volume over the last 5 years has been around 70,000 units. Between 2010 and 2018 the construction volume averaged around 60,000. So it’s clearly an improvement, but is it enough? To find out, we need to look at the change in the housing stock, depicted by the orange timeseries. This statistic includes new builds, office transformations, splitting and unsplitting of apartments and demolition of houses. The change in housing stock is also improving. Over the last 5 years the net addition of new houses was close to 80,000, vs around 60,000 before 2019. So, if you also take into account the demolition of houses, the alternative ways to create houses did have some effect, given that the change in the housing stock is higher than the annual new build volume. But it's clear that the total is not enough to come close to the target of 100,000 new homes a year. So the aim is to increase the change in the housing stock from 80,000 to 100,000. This increase of 25% is maybe not shocking, but in practice its challenging to accomplish this goal given the shortage of labor, strict environmental regulations and the shortage of available land to build on.

New CBS data underscores this conclusion. In the first 6 months of 2024, 32,700 new houses were built. If we simply extrapolate that for the whole year, that would mean 65,400 new houses on an annual basis, a similar volume to 2017. In 2023, 73,600 units were built. That would imply a decrease of more than 10%.

In summary, we support the government's new initiatives and believe the measures should be implemented. However, the above shows that reaching 100,000 new homes per year is ambitious to say the least.

What obstructs the mass production of new houses?

There are three main areas holding back the construction volume.

- Shortage of labor

- Available land area

- Environmental restrictions

As the graph illustrats, during the last couple of years both shortage of labour and materials have been a significant issue. But the graph also shows that since 2023, material shortages (blue) are no longer real issue. Nowadays, labour shortages (orange line) are becoming the main issue.

As one of the most densely populated countries in Europe finding available land area to build on is challenging. With the many protected Natura 2000 areas in the Netherlands, building on forest ground is hardly ever a possibility. That leaves the use of farmland. But this means that in many communities, farmers will have to be forced to give up their farmland through expropriations. This process is likely to take many years as these cases have to go through the courts.

The new governments wants to take more control over deciding which locations across the Netherlands will be made available for construction purposes. Municipalities and provinces will likely have less influence, and possibilities for citizens to appeal against construction projects will be limited.

Lastly, environmental restrictions. In the Netherlands, the rules to protect the environment are strict, especially the nitrogen restrictions. In practice this means that a developer building an apartment block needs to apply for a so called Natuurvergunning (Nature license). In the license application the following needs to be included;

1. A calculated (based on a model of the government) estimate of the amount of nitrogen that will be emitted during the project. As this calculation is rather complicated, an external specialised company needs to be engaged for the application process.

2. The calculated emission of nitrogen needs to be netted. This can be done internally by finding a way to reduce emissions within the project. Or externally, e.g. by using the available emission allowance of canceled projects. Or by purchasing nitrogen allowance from other parties who don’t use them anymore.

In some cases it can take up to 26 weeks (e.g. the province of Gelderland for the developer to get a decision from the province and receive a license. Given the complexity of the application, it’s likely that the province rules that the application is deemed incomplete. That means that the builder needs to restart this whole process from the beginning.

Does this have an impact on construction volumes? The short and simple answer is yes.

Projects [1][2] often get cancelled because it just takes too long or is too costly to get the required licenses.

In conclusion, the Nature license application process is currently too complex and too time-consuming. It’s therefore vital that extra funding will be made available to hire more people to review the license applications. In addition, additional effort is required to simplify this procedure. Both measures would have a significant impact.

[2] Nog geen oplossing stilliggen bouwprojecten door stikstofregels (vastgoedactueel.nl)

The governement allocated €5bn to boost the housing market

For the next 5 years, €5bn is reserved to support the housing market. This funding will be allocated to the following areas:

- Municipalities will receive a realisation incentive. With this new plan, municipalities will get a financial incentive to support housing development, by receiving a fixed amount per home completed.

- Innovative building support: Additional funding will be available for innovative building methods and removing obstacles for housing production.

- Funding will be allocated for the realisation of housing for the elderly.

- For vulnerable areas where large scale housing construction is planned, extra funding is available to make projects economically viable

The €5 billion set aside until 2030 is a good starting point for tackling the housing crisis. However, as the list above shows, there are many different areas that need financial support. With only €1 billion a year, we wonder if the current budget will be enough.

National approach for foundation damage

As mentioned in our previous article, some areas in the Netherlands are prone to problems with the foundations of houses. The government has therefore earmarked €56 million over the next 4 years for a national information center for homeowners who have problems with the foundations of their homes. In addition to informing homeowners, funds will also be made available for foundation inspections in certain areas. It shows that this important topic is on the political agenda. Although we welcome the initiative from the government to support homeowners with this issue, again we think the amount of funds available is rather limited. To illustrate, a proper foundation inspection alone can cost around €5000 per home. Therefore, we believe that solving the problems of foundation damage for homeowners requires a more thorough solution than setting up a national information center.

In conclusion

While the proposed measures may not solve the housing shortage once and for all, the government's initiative is a step in the right direction. The target of building 100,000 new homes per year is ambitious. Achieving this consistently may be challenging due to factors such as labour shortages in the construction sector and the lack of availability of land. Moreover, the €5 billion allocated may not be sufficient and needs to be adjusted for inflation and unforeseen cost increases over the years leading up to 2029.

To have a real impact, the government should broaden its search for solutions. And to underline the point: there are no easy solutions. There is a shortage of labour and available land to build on. In addition, the population is still growing rapidly.

An example of a creative solution that could tick several boxes, would be to make better use of the land that is already built on. In the 60’s and 70’s, many flats have been build that are only 4 or 5 stories high. To make better use of the available land, these flats could be replaced by high-rise buildings. This solution saves all the time that is required to make land available for building. Secondly, the construction time can be reduced. And lastly, this could also offer a solution for affordable housing.